Baltimore’s Water: The Journey

This is the second in our three part series on Baltimore's water and how it relates to brewing beer. Follow these links for information on water sources or water content analysis.

Last week, we traveled from the beer in our glass back to the genesis of our brewing water. To the streams and rivers the City of Baltimore captures to provide a vast amount of freshwater for its citizens and industry. It is this water, from the Gunpowder Falls and Patapsco River (and occasionally the Susquehanna), that makes up the largest portion of our finished beer.

But let’s be honest, we’re not really brewing with river water are we?

Our public waterworks are a massive network of dams, pipelines, treatment processes, filtration mechanisms, and distribution systems all working in concert to deliver clean water to our homes and businesses. Put a glass of water from Loch Raven and one from the kitchen sink side-by-side and I know which one I’d rather put in my kettle. Our water undergoes an enormous transformation before it ends up at our faucet.

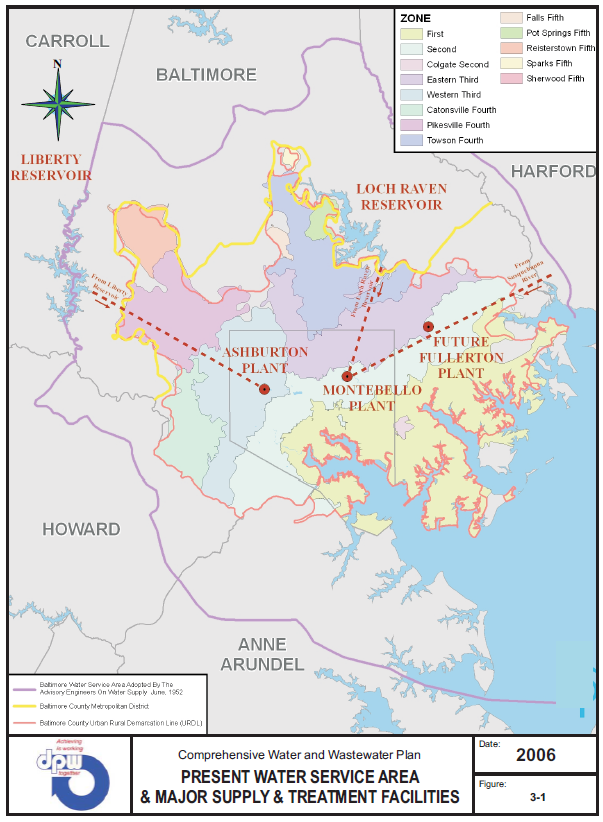

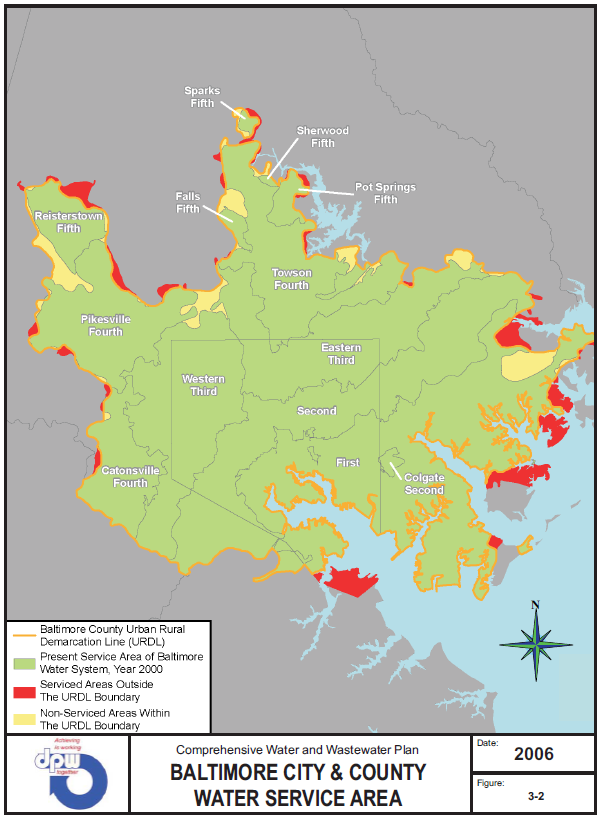

The journey starts when water from the city reservoirs is transferred via underground pipeline to one of the two filtration sites at Montebello or Ashburton. Water from the Loch Raven reservoir is gravity fed to Montebello (plants I and II) while water from the Liberty Reservoir is transferred to the Ashburton Plant. So while the plants may treat the water with the same processes they begin with different supplies.

A map of the Baltimore water service area & supply & treatment facilities.

The reservoirs themselves play the first part in cleaning our water. The dams that feed the filtration plants are a great place for some particulate to settle and rough filters at the reservoir keep out large pieces of debris.

Arriving at one of the treatment plants, the water is subjected to Pre-Chlorination. Chlorine kills bacteria, protozoa, and viruses as well as prevents the growth of algae during the treatment process. The city adds enough of the chemical at the start of the process to target a residual level of 1 ppm chlorine in the distribution network. This level is necessary to prevent any regrowth on route to customers.

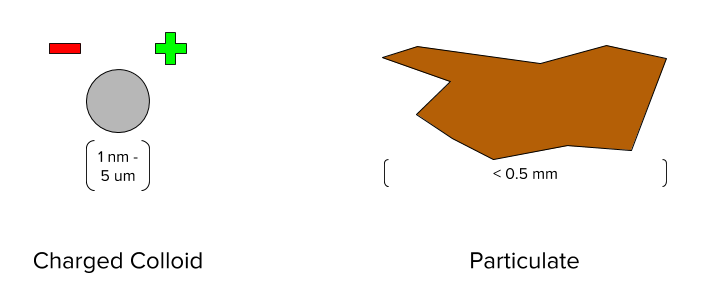

After this preliminary chemical treatment the water is still full of suspended impurities. What are these things and why are the suspended? The impurities are charged colloids and very light particulate. Animal waste, air pollution, and surface runoff are some of the chief contributors of this matter that refuses to sink either because of its charge or its density.

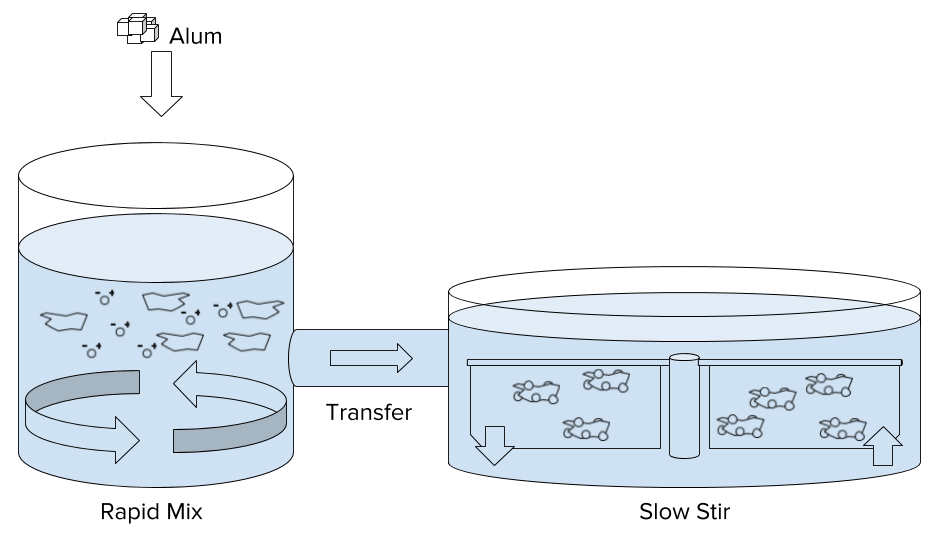

Fortunately, there are methods to encourage the particles to drop out of our water. This step is Coagulation & Flocculation. Aluminum Sulfate (alum) is added to the water which is then rapidly mixed. The solution is transferred into large tanks with slowly rotating paddles that encourage the alum and the particulate into contact. The particulate clumps together and the clumps continue to combine as they encounter each other.

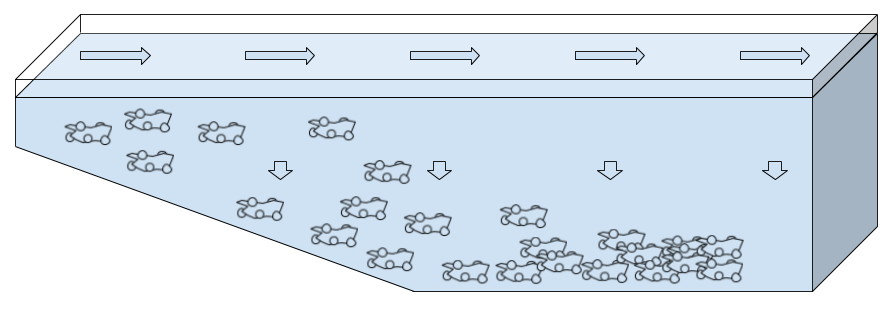

The impurities are now heavy enough to drop out of the water during the next process, Sedimentation. The water is transferred into a set of long tanks where is slowly makes its way from one end to the other. This lazy journey allows the flocculated material to fall to the bottom of the tank just like yeast groups together and drops to the bottom of our carboys as fermentation completes. Water is drawn off the top of the tank, leaving much cleaner than it entered, and the debris is periodically scrapped from the bottom of the sedimentation tanks.

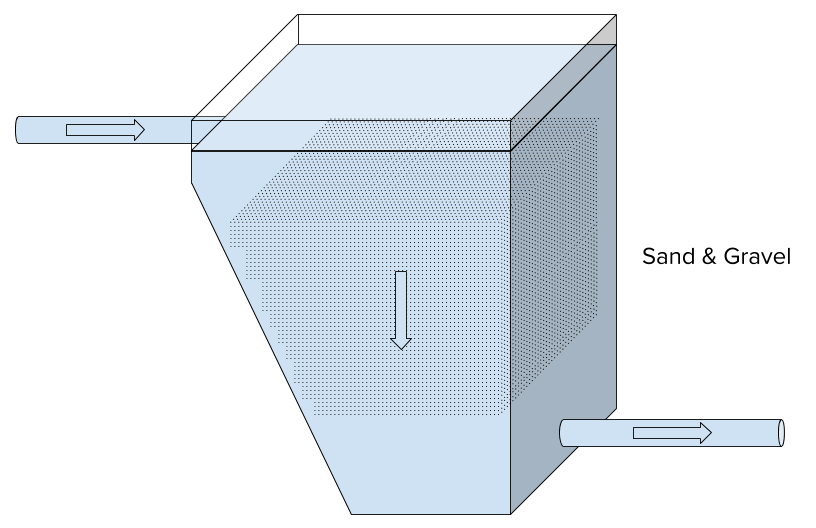

The water is now ready for its last mechanical cleaning process, Filtration. What’s happening here isn’t really much different than what happens when you fill up a filtered water pitcher. The water enters the top and is forced through a bed of sand and gravel, stripping out small particles and other impurities. Clean water exits the system from the bottom and is pumped to holding tanks to undergo final adjustments. Each plant contains a bank of filters which are backwashed on a rotating schedule to clean the filter media and ensure uninterrupted service.

Baltimore City performs three post-filtration adjustments before the water enters the city distribution network. Fluoride is added to the level of 0.7 ppm, Chlorine is added (if needed) to reach a level between 0.2 & 1 ppm, and the pH of the water is raised to 8 using Calcium Oxide (lime). These final adjustments promote dental health, ensure the treated water remains clean as it travels for delivery, and protect against leeching from pipes in the distribution system.

Depending on where your home or business is located in the city you’ll find yourself inside one of Baltimore Department of Public Works many distribution zones.

A map of the Baltimore municipal water zones.

Water from Montebello and Ashburton serves zones 1 & 2 via gravity while being pumped to the others. The cleaned and treated water ends up in taps all over Baltimore City and parts of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, & Howard counties. DPW tests and publishes reports on the water quality & content as it leaves the plants and samples water from taps all over its network to monitor the integrity of the city supply.

So enough already! Baltimore’s waterworks are certainly impressive. A lot of effort goes into the capture, cleaning, and delivering our drinking water. As Baltimore area brewers we’re plenty interested to see what’s in it.

Up Next: Baltimore's Water: The Goods!