Club Posts

Baltibrew Yeast Capture: Into the Lab!

In April we distributed homemade yeast capture kits to the club at our monthly meeting. Our goal? To capture and isolate a strain of yeast native to Baltimore and use it to make a fermented beverage!

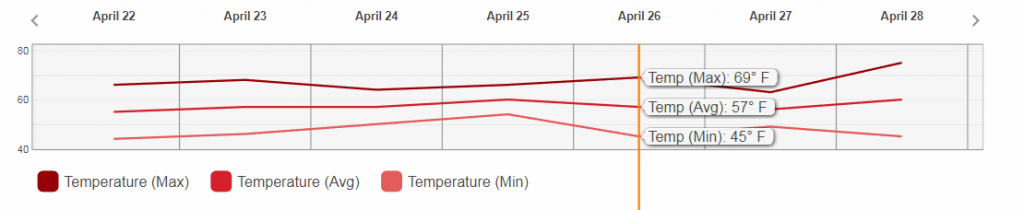

Members were eager to try their luck. The weather was poised to cooperate. Lows would bounce between 40 & 50 F for the next few weeks, a range said to be helpful when harvesting wild yeasts.

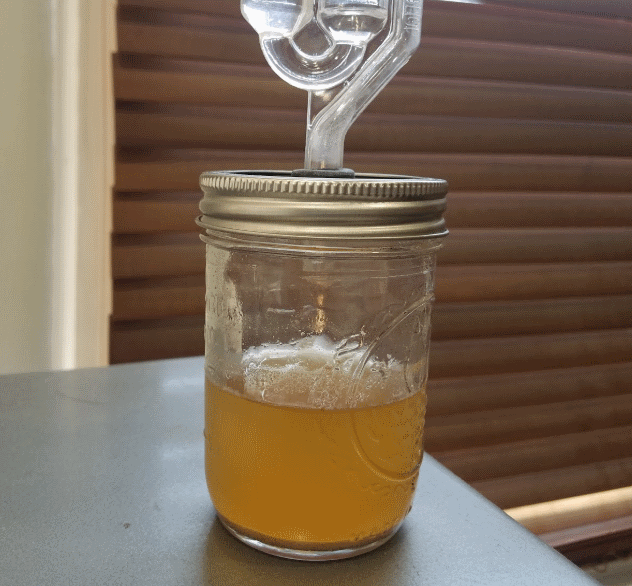

Things were looking up as we grabbed flowers from our backyards & local parks, swabbed out barrels used for coolshipped wort, or left our covered jars tucked safety outside. All that was left for us to do was to sit back and wait for the airlocks to start bubbling. So we waited!

And waited.

And waited.....

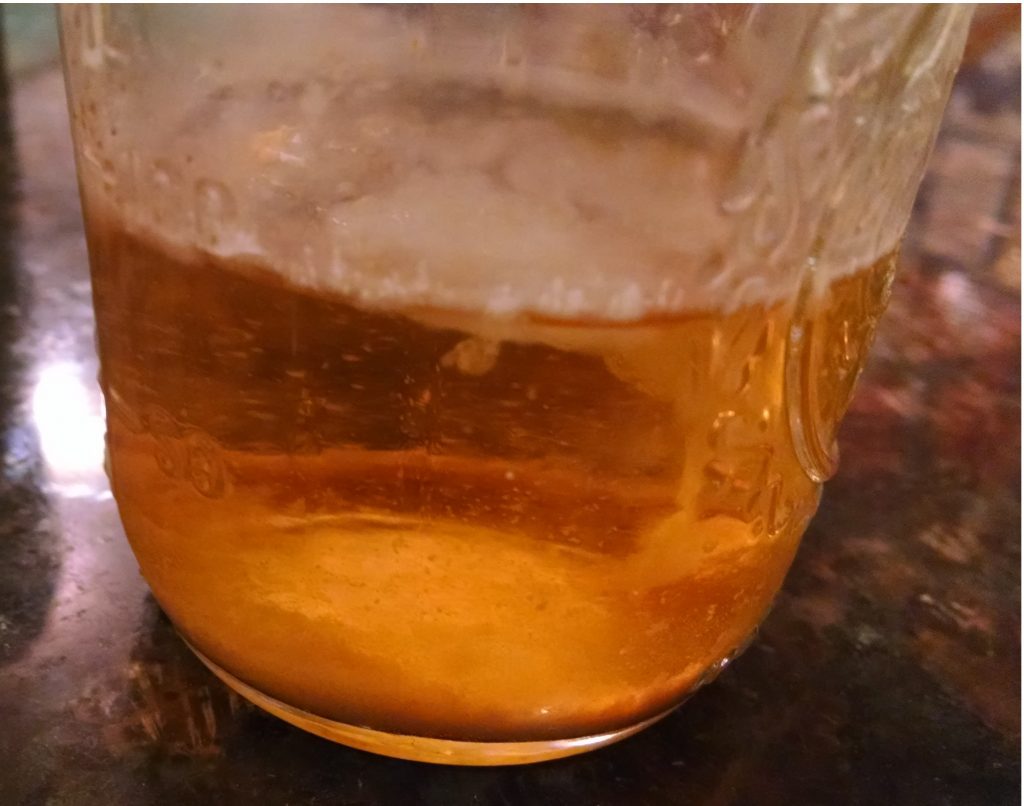

Several members saw no activity at all. Others observed growth of mold or other non-yeast organisms.

This doesn't look too good.

As the reports came in it was clear that we were not going to see widespread examples of obvious & vigorous fermentation. So we began to triage the captures. Anything clearly growing mold was disposed of. The few samples that did report airlock activity were shipped off for early plating. The coolship barrel swabs proved more promising and were left to themselves for a month before streaking. When all was said and done the club selected 4 captures from a total of 16 trials:

- Open Air Capture - Riverside Park

- Kwanzan Cherry Flower - Locust Point

- Coolship Barrel #1 (Big Barrel) - Pikesville

- Coolship Barrel #2 (Little Barrel) - Pikesville

While not the quantity we were hoping for it was nevertheless time to move this party into...

The Laboratory

We're very grateful to Baltibrewer Becky who is doing the detail work on this project. Her first step, check the gravity (all samples stared at a Brix of 6.4 or 1.025 SG):

- Riverside Park - 4.4 Brix/1.017 SG

- Kwanzan Cherry - Negligible change

- Big Barrel - Negligible change

- Little Barrel - 4.2 Brix/1.017 SG

We found it interesting that two samples did not register a gravity drop. They both showed airlock activity, became turbid, and accumulated a layer of sediment on the bottom as activity slowed.

Did we incorrectly measure the first Brix reading? Was there really no decrease in gravity?

A happy capture?

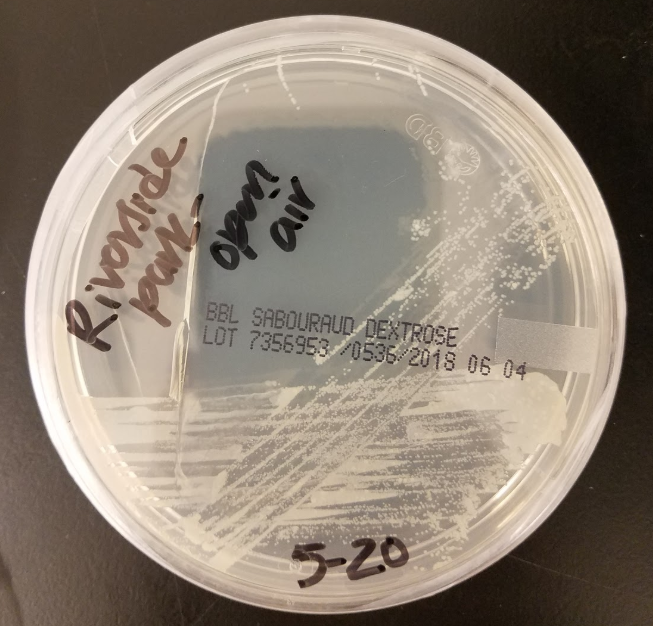

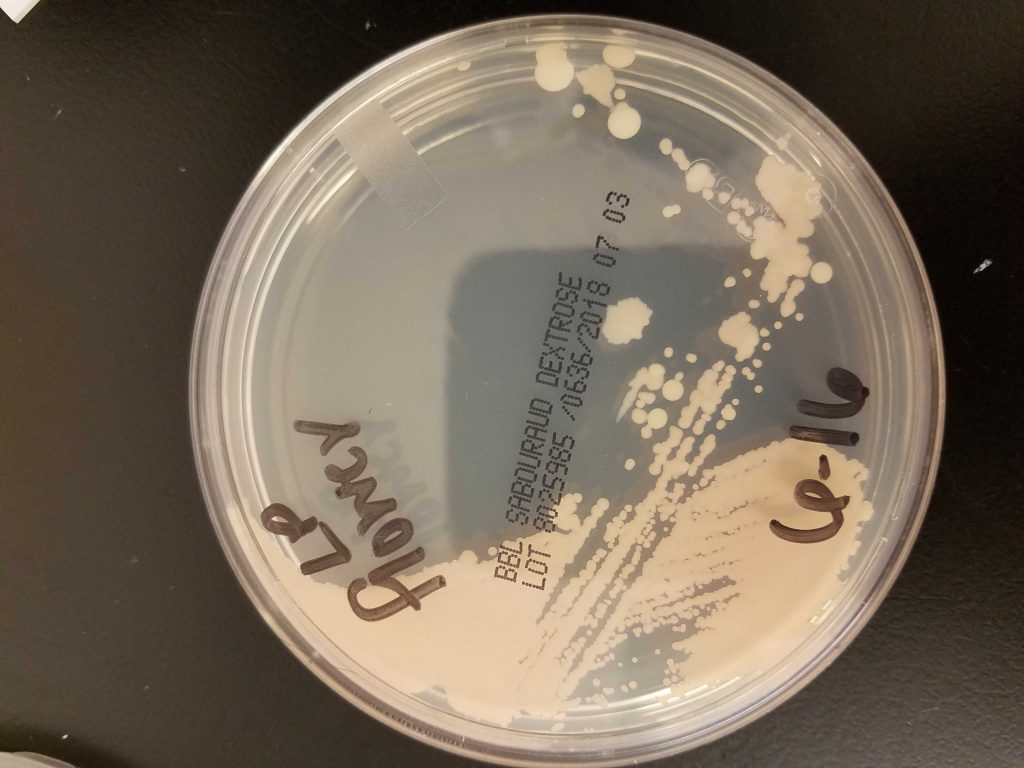

Cultures taken from the samples would tell us more. One drop of medium was transferred to individual Sabouraud Dextrose (Sab) plates. Plates were streaked for isolation and incubated in the dark at room temperature (approximately 68 degrees F). Within days they showed abundant growth.

Open Air (Riverside Park) Plate

Kwanzan Cherry Plate

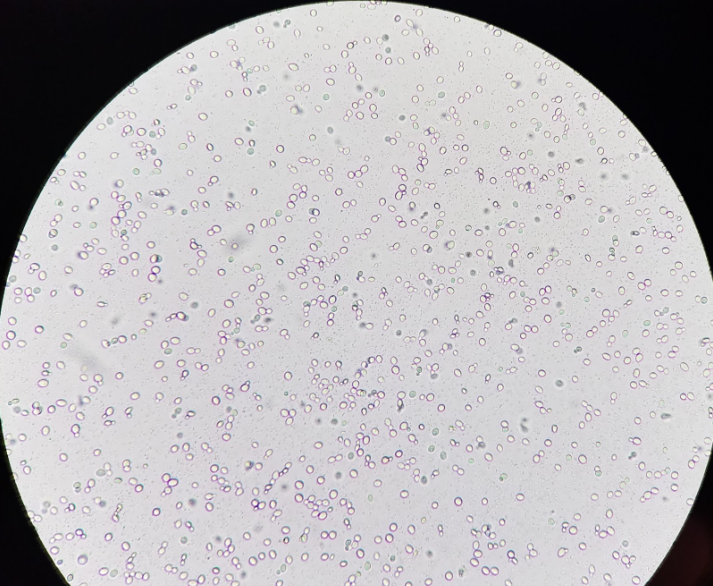

Based on morphology the following organism were identified:

- Riverside Park - 1 budding yeast & 2 types of motile bacteria

- Kwanzan Cherry - 1 budding yeast & 2 bacteria morphologies

- Big Barrel - 2 types budding yeasts & a bacteria

- Little Barrel - 1 apparent pure yeast strain

Success from failure? Possibly.

While the yeast strains are isolated and grown up, it's worth considering what we've accomplished and where we might go from here. The original plan was to isolate native organisms for use in a malt based fermented beverage. We now have at least 2 wild Baltimore yeasts on our plates and 3 more selected from barrels used after coolshipping. Two showed at least moderate attenuative properties in the capture media. Several did not.

Trials will tell us more but it is fair to suspect that these yeasts may not do well fermenting a malt based wort on their own. So is our plan still viable?

Michael Tonsmeire of The Mad Fermentationist blog and Sapwood Cellars (opening soon) stopped by our June meeting to share funky beers and talk about his brewing philosophies. One topic he spoke on was recognizing and embracing your individual strengths and scales.

As homebrewers it can be hard to make an Octoberfest that nails the style as well as commercial brewers. They have first pick of malts, laboratories to grow up strong & pure pitches of yeast, rigorous fermentation & packaging controls, and employees devoted entirely to quality control & sensory evaluation.

On the other hand we are not beholden to the demands of bulk production. This affords us flexibility. For example, we can experiment with secondary additions from local crops, using fruits that aren't grown in large enough quantities to be an option for commercial offerings. Just last month Mulberry Trees in our area started to yield ripe fruit. For anyone not familiar the mulberry is a delicious, mildly sweet & jammy tasting fruit that looks a lot like a blackberry.

Mulberry Fruit & Leaves (Andre Abrahami, May 28th, 2007)

Perhaps we won't end up with a yeast that can make a beer. But perhaps we will end up with several capable of producing local fruit wines and ciders! We will stick to our strengths as homebrewers and stay nimble. Cheers and happy brewing!

Read more as we take our isolates out of the lab for a test drive!

Budding Yeast & Motile Bacteria

June Minutes

Baltibrew General Meeting

June 21, 2018 @ Nepenthe

-

Introductions

-

501c7 Application/Bylaw Revisions Update

-

Our application for 501c7 status was denied by the IRS due to the gross receipts from our charity fundraiser. Greg has reached out to Maryland Nonprofits for guidance and we are waiting to hear back.

-

-

Discussion of Baltibrew Events

-

July 14th/15th - Sensory Classes @ Jon's

Seats are still available. Day 1 will focus on barrel aging flavors. Day 2 will focus on common flavors and faults. 20$ for one session, $35 for two. Talk to Jon to sign up. -

July 28th - Union Collective Opening

-

August 4th - August Brewery Trip

The current plan is to do a local trip, starting at Key around noon the relocating to the Mount Vernon area in the early afternoon to the area of Brew House 16, Charm City Meadworks, The Brewer’s Art, The Brass Tap, & Wet City. We’re exploring options to encourage ridesharing, possibly making a Lyft or Uber credit available to folks who share cars. More to come. -

September 1st - Fall BBQ & Brew @ Jacobs

-

-

Social/Event Updates

-

Annapolis Homebrew Club’s Pints for Paws Homebrew and Craft Beer festival, June 22nd (https://www.eventbrite.com/e/

4th-annual-pints-for-paws- homebrewing-and-craft-beer- festival-tickets-44105596025) -

MDHB Beer Education Classes

-

Recipe Formulation ($10), July 22nd

-

Mike Tonsmeire will also be hosting a session at MDHB in July.

-

-

-

Other New Business/Member Announcements

-

We will have alternate meeting locations later this summer as Nepenthe is moving to their new space. We will meet at the shop one last time in July. The August meeting is TBD and the September meeting is confirmed for De Kleine Duivel.

-

-

Iron Brewer Call for Challengers - Current Iron Brewer - Will

-

Ed Updates

-

Water Wrap Up!

A couple of us visited the Ashburton water treatment plant for a tour. It’s an amazing operation and the staff was very friendly and informative. One items to pass on is that as far as the laboratory chemist was aware there are no changes the chemical protocols when the city pulls from the Susquehanna and the city does not use chloramines to treat the water at this time. We may drop in on the older Montebello plants. -

Baltibrew Yeast Capture

Becky has a few captures plated out in the labs and has detected at least one strain of budding yeast that is likely Saccharomyces. We’re not sure about the attenuation properties of any of the organisms. A back up plan to do a local fruit wine is in the works should we strike out on organisms that can ferment malt.

-

-

Ed Topic - Sour Hour feat/ Michael Tonsmeire (Sapwood Cellars, The Mad Fermentationist, American Sour Beer)!

-

Homebrew Swap!

Baltimore’s Water: The Goods

This is the final entry in our three part series on Baltimore's water and how it relates to brewing beer. Follow the links below for information on our water sources and municipal treatment.

We’ve seen where it comes from.

So let’s talk about Baltimore’s water. What’s in it? And what does that mean for Baltimore area homebrewers?

The Baltimore Department of Public Works publishes a water quality and a water content report annually. The first report demonstrates to the public that the municipal water is safe to drink. The second report provides a mountain of data for anyone interested in a in depth look at what’s coming out of their tap. DPW monitors the water leaving each plant and records monthly data points across 23 different categories.

Using the information from the 36 months beginning in 2015 and ending in 2017, we get a picture of what Baltimore are brewers are dealing with and how it changes over time. The water leaving the Montebello and Ashburton plants is:

- remarkably similar; and,

- remarkably consistent.

Brewing Water Report

As brewers, we tend to focus on a subset of water attributes that are known to have great impact on the brewing process and finished product. The 2017 averages (all measurements are in ppm except pH) for those brewing centric categories are:

| Montebello | Ashburton | |||||

| 2017 | Low | High | 2017 | Low | High | |

| pH | 7.8 | 93% | 102% | 7.8 | 98% | 103% |

| Hardness (CaCO3) | 116 | 96% | 104% | 80 | 93% | 104% |

| Calcium (Ca) | 30 | 94% | 110% | 21 | 93% | 112% |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 9 | 94% | 107% | 6 | 97% | 106% |

| Sodium (Na) | 20 | 88% | 113% | 19 | 91% | 107% |

| Sulfate (SO4) | 17 | 85% | 122% | 13 | 91% | 135% |

| Chloride (Cl) | 53 | 91% | 123% | 42 | 98% | 103% |

Baltimore’s water is low-moderate in hardness and is relatively low in flavor ions (chlorides being the exception). Ashburton water is a touch softer than Montebello, but across the board the water content is largely the same. All told, it’s a great starting point for brewers.

Mr. Consistency

Month-to-month the water changes very little, drifting off its averages about 5% in either direction. Further, when we look year over year, the levels recorded in the data set are quite stable.

| Montebello | ||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 3-Year Avg | Std | % Std | |

| pH | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 0.01 | 0% |

| Hardness (CaCO3) | 106 | 106 | 116 | 109.2 | 5.51 | 5% |

| Calcium (Ca) | 28 | 29 | 30 | 28.9 | 0.87 | 3% |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8.7 | 0.37 | 4% |

| Sodium (Na) | 24 | 21 | 20 | 21.7 | 2.04 | 9% |

| Sulfate (SO4) | 20 | 16 | 17 | 17.9 | 2.08 | 12% |

| Chloride (Cl) | 64 | 52 | 53 | 56.3 | 7.08 | 13% |

| Ashburton | ||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 3-Year Avg | Std | % Std | |

| pH | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 0.05 | 1% |

| Hardness (CaCO3) | 73 | 74 | 80 | 75.5 | 3.55 | 5% |

| Calcium (Ca) | 20 | 21 | 21 | 20.5 | 0.67 | 3% |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5.8 | 0.32 | 6% |

| Sodium (Na) | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19.2 | 0.53 | 3% |

| Sulfate (SO4) | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12.5 | 0.90 | 7% |

| Chloride (Cl) | 43 | 41 | 42 | 42.0 | 1.04 | 2% |

So now that we know what’s in it, what does it mean?

A Tale of Two SRMs

If you’re on municipal water it doesn’t matter much which plant you are drawing from when managing your mash pH. Let’s examine the stories of two very different beers. In both examples, we’ll assume a batch sparge system with 75% efficiency & typical volumes, a target of 5 gallons into carboy, and an original specific gravity reading of 1.050; some fairly common targets and methods.

We’ll start by brewing a pale beer, say a pilsner. For our grist we’ll use 100% Pils Malt and treat our Baltimore tap water with only a Campden tablet for Chlorine. How much Acidulated malt do we need to hit a a target mash pH of 5.3?

- On the Montebello Supply we’d need 5.1%.

- On the Ashburton Supply we’d need 4.9%.

Now let’s consider the other end of the spectrum. A stout with a grain bill of 80% UK Pale, 10% C80, & 10% Roast Barley. How much Acidulated malt do we need to hit a target mash pH of 5.3?

- On the Montebello Supply we’d need 2.1%.

- On the Ashburton Supply we’d need 1.8%.

The amount of Acidulated malt required for each beer is almost identical regardless of the municipal source. Both sources are comparably low in Calcium, Sulfate, and Chloride, making it fairly straightforward to adjust the flavor ions using Gypsum (CaSO4) and Calcium Chloride (CaCl2). Additionally, if the water isn’t soft enough for your brew diluting with to a 1:1 ratio with distilled water will approximate the famous Pilsen water profile to a surprising degree.

Wrapping It Up

All considered, Baltimore’s municipal water is an asset to any local brewer and, with minimal effort, can be tweaked to a variety of profiles. Perhaps it is no wonder that Baltimore developed a rich brewing tradition rapidly after founding.

No matter how you decide to manage your water on brew day we hope this series of articles has shed a little light on the history, operation, and content of the Baltimore municipal water supply. The water here has the potential to make great beer.

Cheers and happy homebrewing!

Caveats

- Baltimore tap water contains low levels of free chlorine. There are many strategies to remove it.

- Baltimore occasionally pulls water from the Susquehanna during times of drought or excess demand. There may be intermittent periods when the water profile differs significantly from the data shown here.

- This data is taken from water leaving the filtration plants. While many of our club members report it as being consistent with water content tests from their home faucets, getting a water report from your tap is the recommended way to calibrate your brewing water calculations.

Sources:

Images:

Baltimore’s Water: The Journey

This is the second in our three part series on Baltimore's water and how it relates to brewing beer. Follow these links for information on water sources or water content analysis.

Last week, we traveled from the beer in our glass back to the genesis of our brewing water. To the streams and rivers the City of Baltimore captures to provide a vast amount of freshwater for its citizens and industry. It is this water, from the Gunpowder Falls and Patapsco River (and occasionally the Susquehanna), that makes up the largest portion of our finished beer.

But let’s be honest, we’re not really brewing with river water are we?

Our public waterworks are a massive network of dams, pipelines, treatment processes, filtration mechanisms, and distribution systems all working in concert to deliver clean water to our homes and businesses. Put a glass of water from Loch Raven and one from the kitchen sink side-by-side and I know which one I’d rather put in my kettle. Our water undergoes an enormous transformation before it ends up at our faucet.

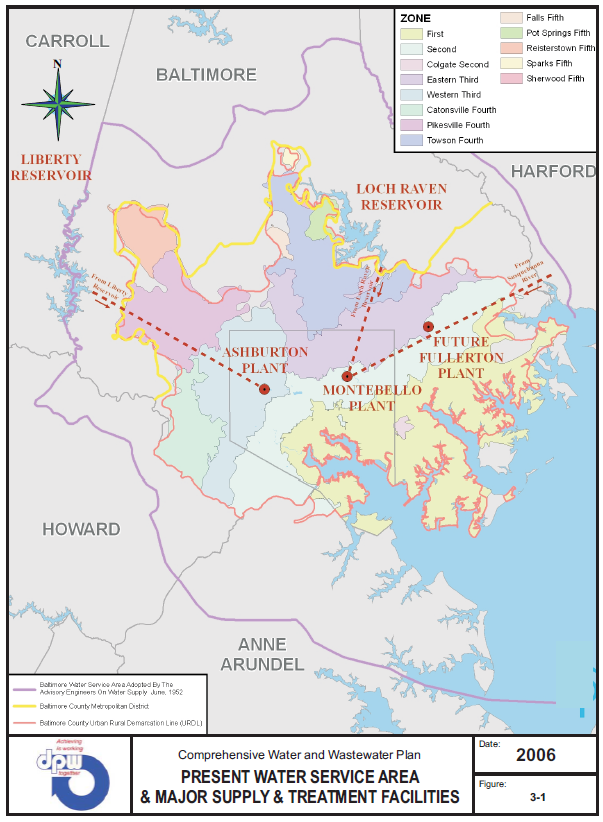

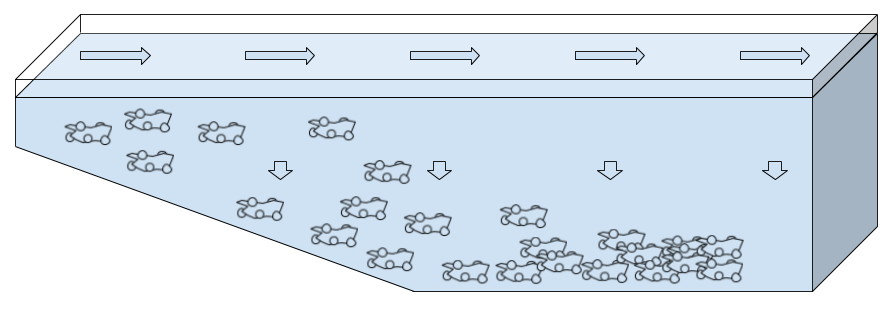

The journey starts when water from the city reservoirs is transferred via underground pipeline to one of the two filtration sites at Montebello or Ashburton. Water from the Loch Raven reservoir is gravity fed to Montebello (plants I and II) while water from the Liberty Reservoir is transferred to the Ashburton Plant. So while the plants may treat the water with the same processes they begin with different supplies.

A map of the Baltimore water service area & supply & treatment facilities.

The reservoirs themselves play the first part in cleaning our water. The dams that feed the filtration plants are a great place for some particulate to settle and rough filters at the reservoir keep out large pieces of debris.

Arriving at one of the treatment plants, the water is subjected to Pre-Chlorination. Chlorine kills bacteria, protozoa, and viruses as well as prevents the growth of algae during the treatment process. The city adds enough of the chemical at the start of the process to target a residual level of 1 ppm chlorine in the distribution network. This level is necessary to prevent any regrowth on route to customers.

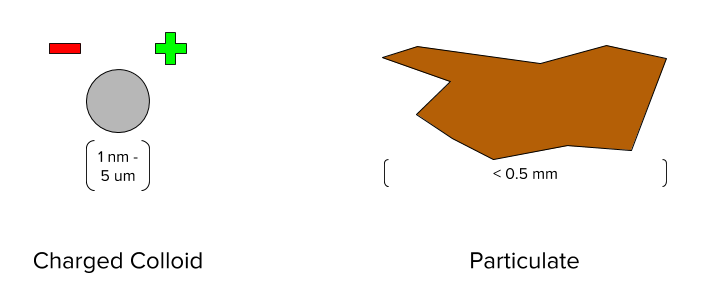

After this preliminary chemical treatment the water is still full of suspended impurities. What are these things and why are the suspended? The impurities are charged colloids and very light particulate. Animal waste, air pollution, and surface runoff are some of the chief contributors of this matter that refuses to sink either because of its charge or its density.

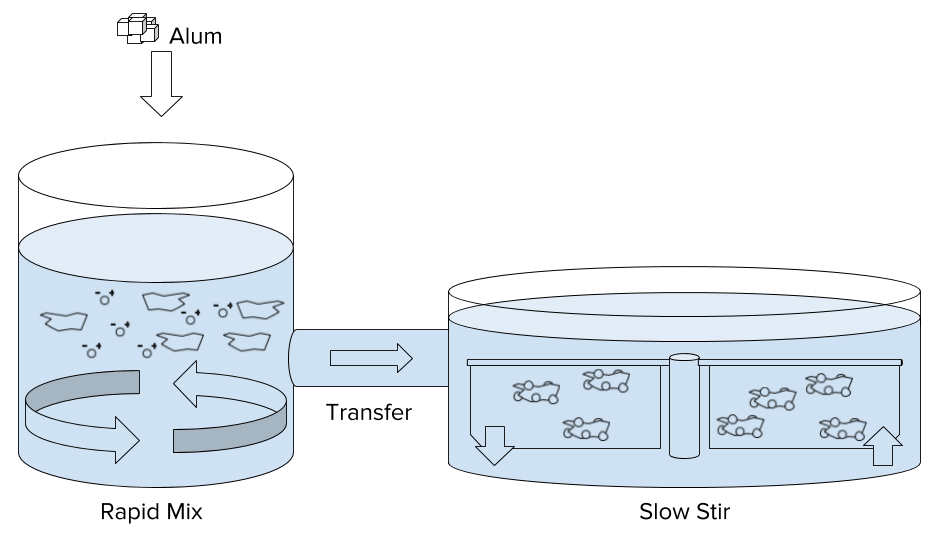

Fortunately, there are methods to encourage the particles to drop out of our water. This step is Coagulation & Flocculation. Aluminum Sulfate (alum) is added to the water which is then rapidly mixed. The solution is transferred into large tanks with slowly rotating paddles that encourage the alum and the particulate into contact. The particulate clumps together and the clumps continue to combine as they encounter each other.

The impurities are now heavy enough to drop out of the water during the next process, Sedimentation. The water is transferred into a set of long tanks where is slowly makes its way from one end to the other. This lazy journey allows the flocculated material to fall to the bottom of the tank just like yeast groups together and drops to the bottom of our carboys as fermentation completes. Water is drawn off the top of the tank, leaving much cleaner than it entered, and the debris is periodically scrapped from the bottom of the sedimentation tanks.

The water is now ready for its last mechanical cleaning process, Filtration. What’s happening here isn’t really much different than what happens when you fill up a filtered water pitcher. The water enters the top and is forced through a bed of sand and gravel, stripping out small particles and other impurities. Clean water exits the system from the bottom and is pumped to holding tanks to undergo final adjustments. Each plant contains a bank of filters which are backwashed on a rotating schedule to clean the filter media and ensure uninterrupted service.

Baltimore City performs three post-filtration adjustments before the water enters the city distribution network. Fluoride is added to the level of 0.7 ppm, Chlorine is added (if needed) to reach a level between 0.2 & 1 ppm, and the pH of the water is raised to 8 using Calcium Oxide (lime). These final adjustments promote dental health, ensure the treated water remains clean as it travels for delivery, and protect against leeching from pipes in the distribution system.

Depending on where your home or business is located in the city you’ll find yourself inside one of Baltimore Department of Public Works many distribution zones.

A map of the Baltimore municipal water zones.

Water from Montebello and Ashburton serves zones 1 & 2 via gravity while being pumped to the others. The cleaned and treated water ends up in taps all over Baltimore City and parts of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, & Howard counties. DPW tests and publishes reports on the water quality & content as it leaves the plants and samples water from taps all over its network to monitor the integrity of the city supply.

So enough already! Baltimore’s waterworks are certainly impressive. A lot of effort goes into the capture, cleaning, and delivering our drinking water. As Baltimore area brewers we’re plenty interested to see what’s in it.

Up Next: Baltimore's Water: The Goods!

Baltimore’s Water: The Genesis

This is the first in our three part series on Baltimore's water and how it relates to brewing beer. Follow these links for information on municipal treatment or water content analysis.

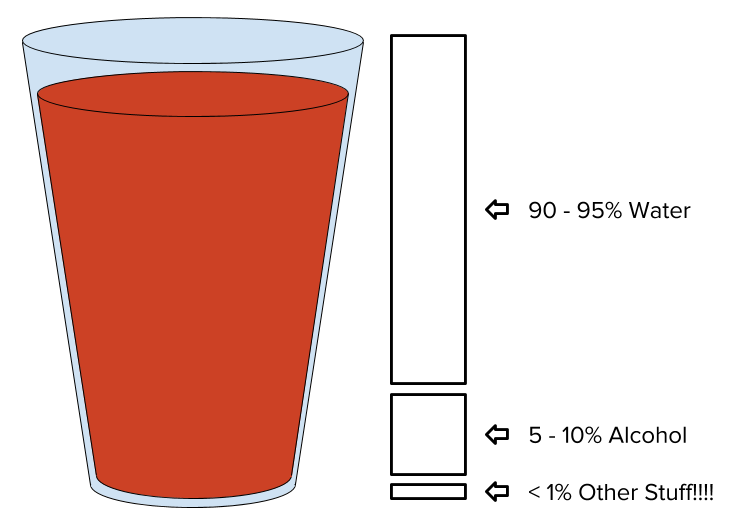

Beer! What is it?

As brewers, we often think of our beers as a recipe: a combination of malts & sugars, hops, yeast, and other flavorings. We talk of phenols, esters, and aromatic compounds that play with our grain bill to produce finished beverages. Our beers can be barrel aged, fruited, dosed with brettanomyces or finished with tinctures of cocoa & vanilla. Yet, when we break a prototypical beer into some very basic categories one item dominates.

Water. Plain. Simple. H2O.

It’s fair to say the other parts of beer add strong flavors and aromas to the drink, driving the character of our finished homebrew. Still, no matter how we choose to craft our recipe and handle the production all those ingredients and processes must sit upon a canvas of water.

The water you brew with has a measurable effect on your final product. It drives interactions in the mash (pH) & boil (break, hop utilization) and affects flocculation & other cold-side processes. It contains flavor ions that contribute character (calcium, sodium, magnesium, sulfates, and chlorides) and shape the profile of the beer.

So what does that all mean to us as homebrewers? There is a boatload of literature and a heap of anecdotes detailing how water affects beer. Baltibrew even had a QC technician from a local brewery come out to give a talk on his philosophy regarding water treatment. For the modern homebrewer information and opinions on how to handle your water abound.

So what about Baltimore's water? It turns out Baltimore water has a reputation as great brewing water!

Let’s dig a little deeper into this aquatic topic. Where does this water come from? How does it get to our faucets? And what’s in it, anyway?

The Baltimore municipal waterworks draw water from three sources, all of which are surface water. The big name in the mix is Loch Raven Reservoir.

Loch Raven Reservoir and dam. It provides drinking water for the City of Baltimore and most of Baltimore County, Maryland.

Located just north of the city, Loch Raven Reservoir and the upstream Prettyboy Dam impound the waters of the Gunpowder Falls. Prettyboy’s function is to keep the level in Loch Raven constant, important because this water is fed to treatment plants via gravity. The two dam system ensures there is enough pressure on the water for it to make the trip via underground pipeline for treatment at one of Baltimore’s filtration plants.

Next up, Liberty Reservoir.

Liberty Reservoir Dam, Baltimore County and Carroll County, Maryland

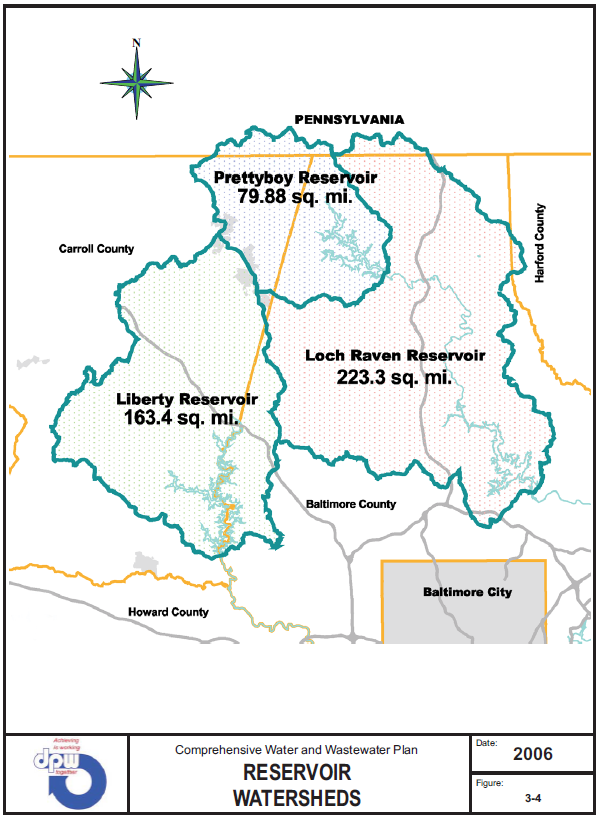

Located to the northwest of the city this dam holds water from the Upper Branch of the Patapsco River. The combined watersheds of these three reservoirs pull water from the north & west of the city and extend as far as southern Pennsylvania.

A map of the Baltimore reservoir watersheds. (2006)

Finally, a pipeline arrives from the northeast that can pump water south to Baltimore from the Susquehanna River. Currently, the Department of Public Works only draw from this source during periods of high demand or drought. Projected growth of the region forecasts the need to pull water from the Susquehanna on a regular basis by 2025. These sources hold 86 billion gallons of fresh water for city and parts of the surrounding counties. They represent over a century's worth of public works projects to secure a quality and consistent water supply for the city.

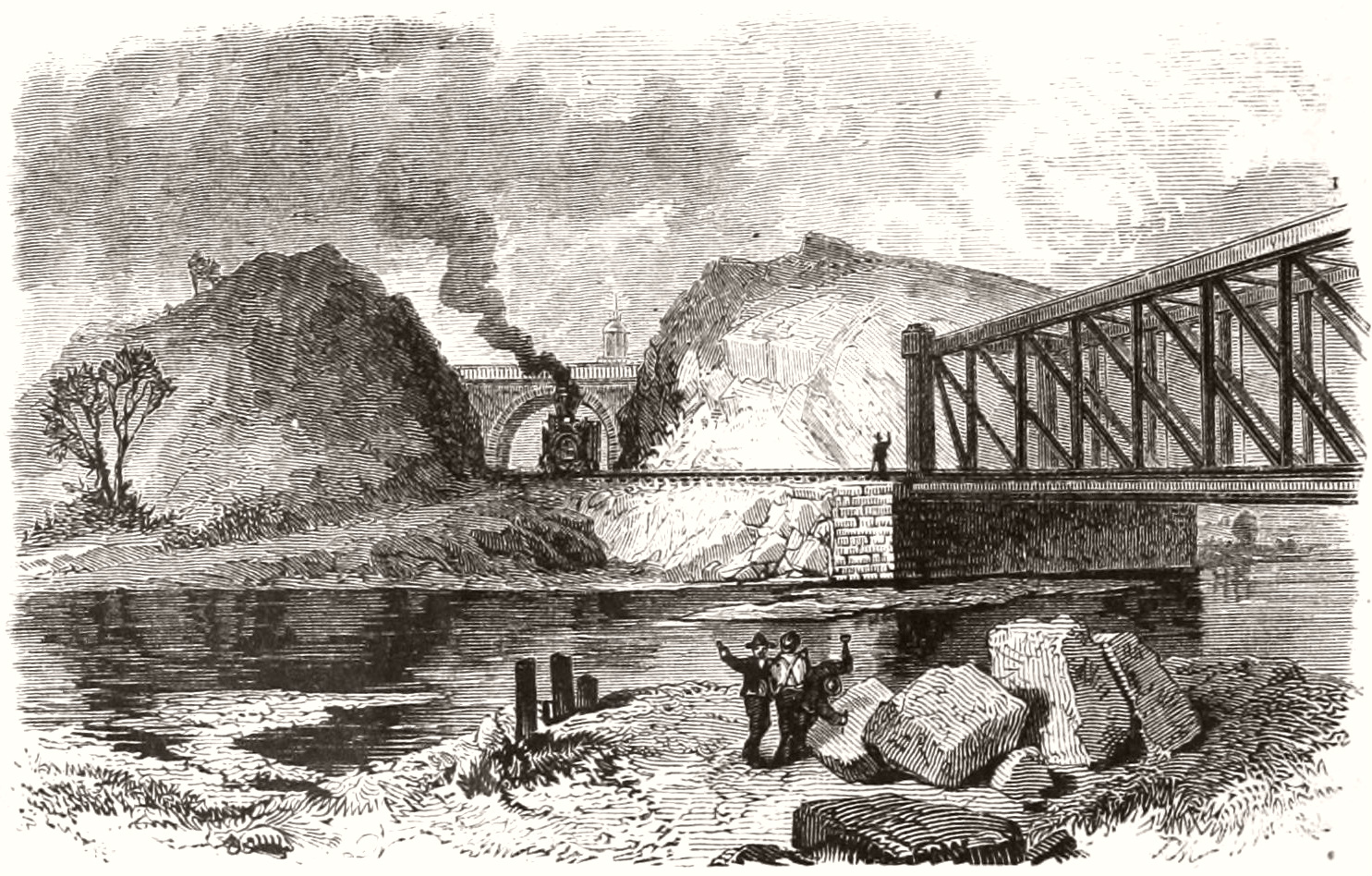

The history of Baltimore's public water supply goes even further into the past and features a name not typically associated with clean, tasty water. The city's first successful water distribution system pulled from the pristine, picturesque...Jones Falls.

A screen placed across Jones Falls traps trash and keeps it out of Baltimore harbor. Although not foolproof-a heavy rain can break the screen-it is effective when cleaned regularly.

Over 200 years ago it looked a bit different (and modern restoration efforts of the Jones are ongoing).

Cut and bridge on the railroad at Jones Falls, Baltimore.

After several failed legislative attempts to create a public waterworks (starting in 1797) a stock company was formed in the early 1800s that impounded the Jones at Calvert & Center Streets. This company improved many aspects of its water system and was eventually sold to the city in 1854 for the sum of $1.35M. Public expansions of the system continued.

The Druid Hill Reservoir was completed in 1873. The Gunpowder Falls was captured in 1881 with Loch Raven Dam completed in 1915. In response to public health concerns the city began chlorination of its supply in 1910. The Montebello Filtration Plants (I and II) went online in 1915 & 1928. To keep up with demand the Liberty Dam was completed in 1954 and the Ashburton Filtration Plant began its operation in 1956. The system now produces 360M gallons of drinking water every day to meet the needs of its residents and business, a true feat of modern engineering.

As Baltimore area homebrewers if you start your brew day by opening the faucet to fill a kettle these are the waters you pull from. Every time we crack a homebrew it is the end of a long journey down the Gunpowder Falls & Patapsco Rivers and through a public water system designed & built over hundreds of years. A journey that passes through our recipes, our kettles & carboys, and ends right in our glass.

Cheers and Happy Brewing!

Next up: Baltimore's Water: The Journey!

Sources:

Images: